June 14th, 2019

The progress made in the development of indicators for the Municipal Atlas of the SDGs in Bolivia highlights the fact that the Andean region is lagging behind in several respects. It stands out for its high poverty and inequality levels, reduced budgetary execution capacity at the municipal level, high levels of child malnutrition, high infant mortality rates and alarming levels of emigration.

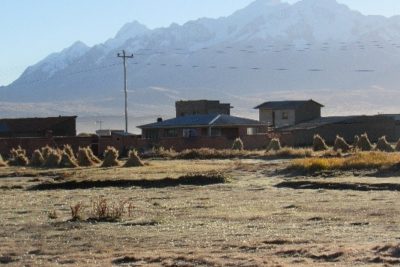

In view of this, we visited some of the municipalities around the Titicaca lake in order to approach the reality that the numbers and indicators draw for us. We visited Achacachi, Huarina, Ancoraimes, Escoma, Mocomoco and Carabuco. In all those municipalities we find that the population has aged and that most of the youth are migrating into big cities or other countries in search for better opportunities.

In Carabuco and Escoma we found the Asociación Familia de Artesanos Don Bosco, an association led by an Italian family representing the Operación Mato Grosso organization, founded in 1967. They call themselves a suigeneris youth movement and highlight their character as a formative movement for youth. The Director, Stefano Zordan, tells us that this is a group of volunteers that focuses efforts in Peru, Ecuador, Brazil and Bolivia (Carabuco and Escoma), where projects are small but with high social and economic impact. The organization is closely linked to the Salesian order, the bishopric and the Bolivian episcopal conference, given that its founder, Ugo de Censi, was a faithful follower of Don Bosco.

In Carabuco, the Zordan family is in charge of a private secondary school. At first, we were perplexed by the existence of a private school in one of the poorest municipalities in Bolivia -In 2012, 86.6% of the population did not have access to basic needs and in 2016, 83.7% of the homes were under conditions of Extreme Energy Poverty.

Zordan explains that despite being private, the Don Bosco Workshop Educational Unit offers its services free of charge to all its students and is exclusively aimed at benefiting children with scarce resources from communities belonging to several municipalities in the area. It is a boarding school that children return to on Sunday afternoon and leave every Saturday morning. While in school, children are guaranteed food, accommodation and instruction, all for free. Zordan says they gained the communitys’ trust since 1994 when the school was opened for the first time.

One of the main problems the Italian organization encountered in the Bolivian Highlands, is that “… migration of young people is the reality of the countryside. For young people, there is no dream. In that sense 20, 30, 40 years ago, people worked on their farms, in agriculture, or fishing… and they used to stay here. Now with the advent of the internet and communication, young people see the possibility to have different things. They say: ‘I also want a nice house; I want to give my children a better life and education’. So, young men finish high school and leave. There is no industry, there is nothing for them here. The soil is difficult and dry. You can build greenhouses, but working the land is very hard and young people do not want to do it.”

One of the main problems the Italian organization encountered in the Bolivian Highlands, is that “… migration of young people is the reality of the countryside. For young people, there is no dream. In that sense 20, 30, 40 years ago, people worked on their farms, in agriculture, or fishing… and they used to stay here. Now with the advent of the internet and communication, young people see the possibility to have different things. They say: ‘I also want a nice house; I want to give my children a better life and education’. So, young men finish high school and leave. There is no industry, there is nothing for them here. The soil is difficult and dry. You can build greenhouses, but working the land is very hard and young people do not want to do it.”

The schools’ goal is to provide youth with quality technical and professional training as a way of incentivizing them not to leave the community. Through training in the art of carpentry, mosaics and embroidery, upon graduation students acquire enough skills for their own livelihoods. Once they graduate from high school, where they comply with all regulations required by the ministry of education, they have the possibility to stay in the workshop as artisans either in Carabuco or in Escoma. They are given the opportunity to earn a salary by crafting sculptures, furniture or mosaics for distribution in the national market, thus making life in the countryside viable.

The association created in the year 2000 is responsible for the nationwide distribution of the workshops’ production. There are already 40 artisans who decided not to leave Carabuco after graduating from the boarding school. As a result, 40 families are living and activating the local economy. Greater demand for services and trade is perceived. In general, more human activity is perceived, thus promoting development in the community. The municipal Kindergarten, Zordan says, is full of the artisans’ children, unlike other villages, where schools are becoming empty.

to leave Carabuco after graduating from the boarding school. As a result, 40 families are living and activating the local economy. Greater demand for services and trade is perceived. In general, more human activity is perceived, thus promoting development in the community. The municipal Kindergarten, Zordan says, is full of the artisans’ children, unlike other villages, where schools are becoming empty.

The school is funded by donations from the Italian organization. On the contrary, the association is self-sustained and depends entirely on the young artisans’ work. High sums are charged for the beautifully hand-crafted products and only the best inputs are used in every piece they produce.

Besides paying the artisans’ salary with the workshops’ income, the Zordan family provides them with access to additional financial resources to build their homes in the community. Given the regulation of rural lands in Bolivia, rural landowners do not have access to affordable housing credits as people do in the metropolitan areas. Only the use of rural land is guaranteed by law, not the disposition of it. Rural landowners do not own the land rights, making it impossible to access a mortgage loan or a so-called social housing credit, ironically intended for the poorest segments of society. Instead, the minimum interest rate they have access to is 20%. Despite these regulations, land transactions in the rural area are possible, as unreliable as they are, they do not have the documented support or the public registry that helps avoid conflicts between both parties involved in the transaction. The point being is, that thanks to the loan the association makes available to them with the money they themselves generate, young artisans have the possibility to acquire land and build their homes near their work source. Zordan says to this: “Of the small profit the association makes, 99% we use to lend to artisans to build their houses and support their children. Actually, we give away the money, we don’t lend. If they can and manage to pay it back, it is okay… if not, it’s not in our interest to get it back. We’re not a bank. The goal is for families not to migrate… for them to stay here”.

Besides paying the artisans’ salary with the workshops’ income, the Zordan family provides them with access to additional financial resources to build their homes in the community. Given the regulation of rural lands in Bolivia, rural landowners do not have access to affordable housing credits as people do in the metropolitan areas. Only the use of rural land is guaranteed by law, not the disposition of it. Rural landowners do not own the land rights, making it impossible to access a mortgage loan or a so-called social housing credit, ironically intended for the poorest segments of society. Instead, the minimum interest rate they have access to is 20%. Despite these regulations, land transactions in the rural area are possible, as unreliable as they are, they do not have the documented support or the public registry that helps avoid conflicts between both parties involved in the transaction. The point being is, that thanks to the loan the association makes available to them with the money they themselves generate, young artisans have the possibility to acquire land and build their homes near their work source. Zordan says to this: “Of the small profit the association makes, 99% we use to lend to artisans to build their houses and support their children. Actually, we give away the money, we don’t lend. If they can and manage to pay it back, it is okay… if not, it’s not in our interest to get it back. We’re not a bank. The goal is for families not to migrate… for them to stay here”.

This is a way in which we were able to understand how poverty manifests itself in the Bolivian Highlands. We also had the opportunity to see how small, but effective efforts can make a difference in reversing migration processes.

———————————————————————————————–

* Lily Peñaranda, M.Sc., Chief Development Manager, SDSN Bolivia.

The viewpoints expressed in the blog are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of their institutions. These posts are part of the project “Municipal Atlas of the SDGs in Bolivia” that is currently carried out by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) in Bolivia

Español

Español