August 22nd, 2019

Each year, towards the end of the dry season, Bolivian farmers burn forest and other vegetation to prepare for the next agricultural season. Slash-and-burn agriculture is a traditional farming technique that begins by cutting down the trees and woody plants in an area. The downed vegetation is then left to dry, and before the rainy season starts, the debris is burned, resulting in a nutrient-rich layer of ash which makes the soil fertile, and also temporarily eliminates weed and pest species. After some years of cultivation, nutrient contents fall and weed infestation increases, and the plot is left to grow into forest again. This practice works well on a small scale, but can be disastrous at a larger scale, and can accidentally cause out-of-control wildfires.

This is what Bolivia is suffering right now. Forest fires are ravaging more than 500,000 hectares in the Santa Cruz department, which is why the department has declared a state of emergency due to out-of-control wildfires. Particularly affected are the municipalities of Roboré, El Trigal, Pampa Grande, San Ignacio de Velasco and San Rafael who also declared themselves in a state of municipal emergency.

Due to the dry weather and strong winds, fires expand far beyond the plots on which fire was intended. Currently, human settlements and protected areas are also affected by forest fires, which are completely overwhelming the limited response capacity of the Departmental Emergency Operations Center (COED).

As we have seen repeatedly in the news lately, even rich countries with massive resources find it almost impossible to fight forest fires (1). Therefore, it is unrealistic to expect that a few Bolivian helicopters, appointed to help put out the fire, will make a difference. Similarly, after more than a week of fires, it is difficult to know whether even the American Supertanker will have a significant effect. If the government of France couldn’t even protect their treasured Notre Dame in the middle of a wealthy city, the natural and human made treasures of the Chiquitania are facing long odds.

The current situation should not come as a surprise to anybody, though. Bolivia has been burning forests more and more aggressively for decades to expand the agricultural frontier. While intact Amazon rainforest is quite fire resistant, this is not the case for the fragmented forests at the drier areas at the border of the rainforest. If hundreds of thousands of hectares of transitional forests are intentionally burned, not only are huge amounts of CO2 emitted into the atmosphere, but the habitat of the biodiversity that resides there is systematically destroyed. Moreover, as has been the case with other fires around the world, it is only a matter of time before fires come out of control and cause huge human, economic and cultural losses.

The question arises whether the benefit that the Bolivian society receives from the soy beans and livestock in Santa Cruz takes into account the costs of the enormous loss of biodiversity and environmental services. Not only would they have to be enough to pay the direct costs of the Supertanker rental, the countless hours of helicopter flights, the lost cattle heads, etc., but also the indirect costs that will arise after the fires, when those same regions experience stronger flooding and droughts due to the lack of vegetation cover to regulate the water cycle.

To reflect this threat, we are including several indicators related to deforestation in our Municipal Atlas of the SDGs in Bolivia. We have updated all the indicators to include information from 2018.

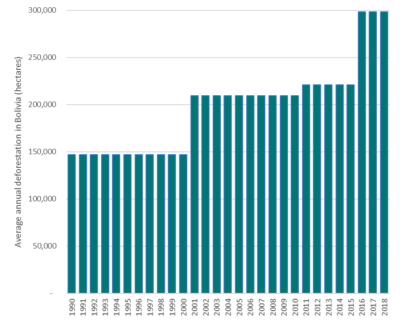

Figure 1 shows how annual deforestation has increased in Bolivia from an average of about 150,000 hectares per year during the 1990s to almost 300,000 hectares per year during 2016-2018. These are averages over several years, since there is a lot of random variation from year to year, mostly due to climatic variations and the dynamics of land use, and these random variations obscure the overall trend. For example, 2016 represented the highest level of deforestation in Bolivia ever, with more than 417,000 hectares deforested, but the number fell to about 263,000 hectares in 2017 and 215,000 in 2018. But in 2019, it looks destined to increase again due to out-of-control wildfires. Thus, we believe that the averages over several years provide a better idea of the general trend.

Figure 1: Average annual deforestation in Bolivia, 1990-2018 (hectares/year)

Source: Authors’ estimation, based on the sources cited in the footnote (2).

Source: Authors’ estimation, based on the sources cited in the footnote (2).

In the rest of the article we will focus on data for the last three years (averaging 2016, 2017 and 2018) and explore in more detail which municipalities recently recorded high deforestation levels.

We present the data in three different ways:

- Absolute levels of deforestation (hectares);

- Deforestation rates (annual deforestation as a percent of forest in 2015), and

- Deforestation per capita (m2 deforested per inhabitant per year).

In each of the cases we present the 25 municipalities with the highest deforestation between 2016 and 2018.

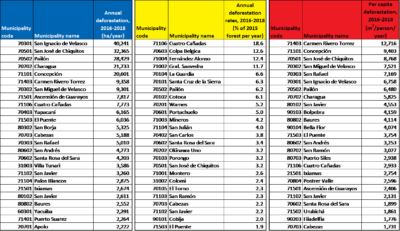

The blue column in Table 1 shows the 25 municipalities with the highest levels of deforestation in absolute terms (hectares/year). These 25 municipalities are responsible for 80% of total deforestation in Bolivia between 2016 and 2018. Of these, 16 are located in the department of Santa Cruz, the rest comprise municipalities in the following departments: 4 in Beni, 3 in La Paz, 1 in Cochabamba and 1 in Tarija.

The yellow column shows the 25 municipalities with the highest rates of deforestation (% of the existing forest in 2015). 23 of the 25 municipalities with the highest rates of deforestation are located in the department of Santa Cruz, while the remaining two are located in the departments of Cochabamba and Pando.

Finally, the red column shows the 25 municipalities with the highest rate of deforestation per capita (m2/person/year). Again, we see that most of the municipalities on this list are located in the department of Santa Cruz, but there are also some in Beni, Pando and La Paz.

Table 1: The 25 Bolivian municipalities with the highest levels of deforestation between 2016 and 2018, according to the three deforestation indicators.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Table 1 shows three different ways to measure the intensity of deforestation. High levels of deforestation in absolute terms can be justified if the municipality has a large population. However, if a municipality is on the list of municipalities that most deforest in all three columns, deforestation is certainly considered to be high in that municipality from any point of view. This means that in such municipalities the environmental impact will be great in the short term.

In total, 50 different municipalities have made it to one of the Top 25 lists of deforestation in Table 1 above, and 7 made it to all three lists. These 7 municipalities with high deforestation, by any measure, are all located in the department of Santa Cruz and they are the following:

- San José de Chiquitos

- Pailón

- Santa Rosa de Sara

- Cabezas

- San Javier

- Cuatro Cañadas

- El Puente

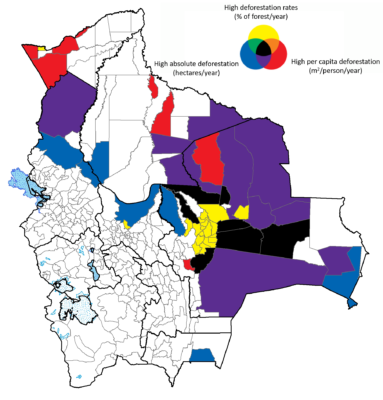

Map 1 shows in how many, and in which dimensions, each municipality in Bolivia have made it to one of the Top 25 lists above. Each dimension is represented by one of the primary colours (blue, yellow, red), but if a municipality appears on more than one list, it is coloured in the composite colour that arises from mixing the two primary colours. There are a lot of purple coloured municipalities, for example, which implies that they are both on the red list (high per capita deforestation) and the blue list (high absolute levels of deforestation). The 7 municipalities that made it to all three lists are coloured in black.

Map 1: Municipalities listed on one or more of the three lists of municipalities that deforest the most in Bolivia, 2016-2018.

Source: Developed by the authors based on information from Table 1 above.

Source: Developed by the authors based on information from Table 1 above.

Three of the municipalities that are currently in a fire-induced emergency (Roboré, El Trigal, and Pampa Grande) were not among the worst deforesters themselves during 2016-2018, but they are located close to some of the worst deforesters, and, unfortunately for them, fire does not respect borders.

—————————————————-

*The Sustainable Development Solutions Network – Bolivia

* Conservation International – Bolivia

The Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) in Bolivia is currently preparing a Municipal Atlas of the SDGs in Bolivia. It is a significant collaborative effort involving many different institutions. The viewpoints expressed in the blog are the responsibility of the authors and may not reflect the position of their institutions. Readers are encouraged to provide feedback to the overall coordinator of the Atlas, Dr Lykke E. Andersen, Executive Director of SDSN Bolivia at: Lykke.E.Andersen@sdsnbolivia.org.

————————————

- For example, the Camp Fire in California last year destroyed about 60,000 hectares, but since it was close to densely populated areas, it was the most costly (USD 16.5 billion) and deadly (at least 86 persons died) in California’s history. The same year, British Columbia in Canada lost more than 3 million hectares to wildfires, breaking the record of the previous year, where 1.2 million hectares burned, and 65 thousand people were forced from their homes. This year, at least 3 million hectares of forest has burned in Siberia, causing massive CO2 emissions, but fortunately few human casualties.

- Data sources: Data for 1990-2010 are from SERNAP & CI (2013) Deforestación y regeneración de bosques en Bolivia y en sus Áreas Protegidas Nacionales para los periodos 1990-2000 y 2000-2010. La Paz: Servicio Nacional de Áreas Protegidas, Museo de Historia Natural Noel Kempff Mercado y Conservación Internacional – Bolivia. Data for 2011-2015 are from the Bolivian Ministry of Environment and Water (Sala de Observación – OTCA, Dirección General de Desarrollo Forestal y Autoridad de Bosques y Tierras 2017). Finally, data for 2016 to 2018 are from the Hansen Global Forest Change data set version 1.5.

Note: Only municipalities with more than 0.1 km2 of forest have been included in this analysis.

Español

Español