With huge efforts and investments, Bolivia has achieved fairly high electricity coverage. According to the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, in 2016, 93% of the population had access to electricity (1), and if the trend continues as it has the past 6 years, the country would have almost complete coverage in 2025.

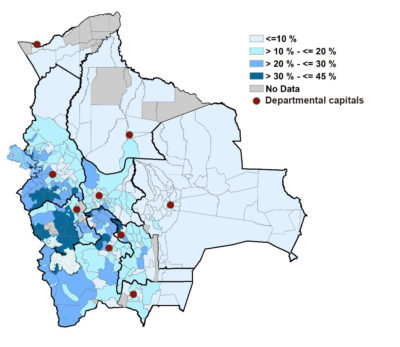

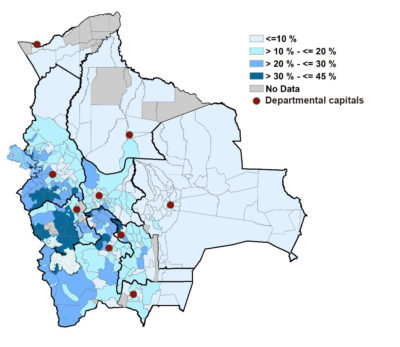

However, by analyzing the data from residential electricity meters across the country (2), we find that in many places in Bolivia the access to electricity is not fully taken advantage off. In fact, around a quarter of all municipalities in Bolivia registered more than 20% of homes with zero consumption during the month of May 2016, which suggests temporarily empty homes. As can be seen from the map below, empty homes are concentrated mostly in the Bolivian highlands, in the south-western part of the country. In contrast, in the lowlands of Bolivia, the percentages of zero-consumption are generally below 10%. In capital cities the percentage of zero-consumption generally ranges between 4% and 6%, except for El Alto, where it is 9%.

Map 1: Proportion of residential electricity meters with zero electricity consumption during May 2016, per municipality.

Source: Andersen, Branisa & Calderón (2019). Map kindly elaborated by José Acuña.

Source: Andersen, Branisa & Calderón (2019). Map kindly elaborated by José Acuña.

The electricity consumption data seems to indicate a process of incomplete migration in Bolivia. Many people migrate in search of better opportunities, mainly to the 50 municipalities listed in the article titled “

The most attractive municipalities in Bolivia“, but also across international borders. People embark on this migratory process, apparently, without losing the strong ties with their communities of origin. As described in another

poverty-related article, this could be related to laws that apply to rural property rights, mainly in the Highlands. People are only allowed to transfer the land to other members of their family through inheritance, which not only implies a process of excessive fragmentation of the land, leading to extremely small properties that do not cover for the most basic necessities for the owners, but also establishes a strong and almost unbreakable bond between the rural community and the Individual.

Another obvious reason which may help explain the empty home phenomenon, is the climate in the Highlands, which is known to be very dry and cold during the winter and does not easily allow for agricultural activities. The lack of alternative options in the area makes people look for different activities in the city.

To better understand the dynamics of migration in the Highlands, we decided to visit some of the most peripheral neighborhoods of the city of El Alto, considering that El Alto is the

second most attractive destination for those who decide to leave their homes in other municipalities or towns.

We were able to visit the neighborhoods of

San Roque and

Villa 10 de Mayo, which are located on the road towards Copacabana, a municipality near the Titicaca lake. It was hard to find homes with people, but we did gain access to five households whose members gave us their time to answer a few of our questions.

In all cases, the families came from villages far from the urban centers of the following municipalities: Umanata (La Paz), Pucarani (La Paz), Huayllamarca (Oruro) and Achacachi (La Paz). In two of the cases the villages of origin of the families had no direct access to any road. According to these interviews, the main reason for emigration is access to work and economic resources, not very different from any other economic migrant in the world. However, listening to their testimonies provides more vivid images of the variety of situations that have caused them to migrate.

A main problem at their places of origin is the small property sizes that does not allow for efficient levels of production. In addition, yields tend to be low due to climatic constraints, and prices of the typical native products, such as potatoes, in the domestic markets are low. Raising livestock is not feasible on such small plots either. As another important aspect, most interviewees highlight climate change and a higher frequency of freezing temperatures as an impediment for cultivation. In the words of a father (38) of 6 children “

The village (Ticati, Umanata) is empty; only elderly people remain there“.

On the other hand, of the 5 families interviewed, 3 have close relatives that migrated abroad, with the main destination being the neighboring country of Argentina and the second most important destination, Brazil. In almost all cases, migrants said they would return to their places of origin if they had better working and economic conditions, and highlighted their intention to return to their community if the economic situation did not improve in the city. In general, they do not want to lose the link with their place of origin and all interviewees return more than 5 times a year, and some even more than once a month. As an example, one of the women interviewed (54) currently has the position of Bartolina (3) in the municipality of Achacachi, despite having moved to El Alto 18 years ago.

Although these few interviews do not provide sufficient evidence for firm conclusions, the empty homes, as evidenced by the many electricity meters with zero electricity consumption, do suggest that current land regulation may create poverty traps in rural areas, and probably prevents a much needed land consolidation process from happening, which could allow the establishment of rural land holdings of more profitable and sustainable size.

Notes:

(1) See this

link.

(2) The data comes from the Viceministry of Electricity as inputs for a project that we are developing with the Center for Social Research (CIS) of the Vicepresidency.

(3) Bartolina is a woman, generally with indigenous origins, that holds a high ranking political and administrative position in the Aymara culture and is currently recognized by the country’s constitution and as an official representation in indigenous communities.

———————————-

* Lykke E. Andersen, Ph.D., Executive Director OF SDSN Bolivia.

** Guillermo Guzmán, Ph.D., Centro de Investigaciones Sociales (CIS) de la Vicepresidencia del Estado.

*** Lily Peñaranda, M.Sc., SDSN Bolivia, Co-Editor of Municipal Atlas of the SDGs in Bolivia, Coordinator of the Master’s Program in International Relations for the Faculty of Political Sciences (UMSA).

The viewpoints expressed in the blog are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of their institutions. These posts are part of the project “Atlas of the SDGs in Bolivia at the municipal level” that is currently carried out by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) in Bolivia, of which CIS is a member.

Source: Andersen, Branisa & Calderón (2019). Map kindly elaborated by José Acuña.

Source: Andersen, Branisa & Calderón (2019). Map kindly elaborated by José Acuña.